A funny thing happened on the way back from the Antarctic High Plateau

The weather has improved for the scientists at the coast, Denis Lombardi finally has some good news, and Jos Van Hemelrijck learns why covering up properly in Antarctica is important for your health.

Good news from the coast

First and foremost, we’re happy to report good news from the coast. Wednesday it stopped snowing, and scientists from the IceCon project at the ULB have made good progress extracting ice cores on Derwael Ice Rise.

Yesterday they finished drilling the first 30-metre ice core, and today (Friday), they’re working on drilling a second one. Meanwhile, Nicolas Bergeot set up his GPS observatory on the ice and Frank Pattyn and Brice Van Liefferinge are scanning the ice layers of Derwael Ice Rise with their radar machines.

Now or never!

Keeping an eye on the weather forecast, we knew that Thursday would be the best day of the week at the Princess Elisabeth station. Seismologist Denis Lombardi had two more seismic observatories to service up on the high plateau, a fair distance away from the station. It’s impossible to go up there in bad weather. One observatory is on the southern flank of the Sør Rondane Mountains, while the other is way out on the ice, 70 km from the station. So on Thursday morning, BELARE team leader Alain Hubert decided it was our only chance to make a dash for the plateau before bad weather returned, so we went for it.

After breakfast, Alain, Denis and I rode off on skidoos. We first went out to Teltet Nunatak, a hill 6 km east of the station. From there, we turned right and made for Gunnestad Breen (a breen is a glacier in Norwegian). Alain had taken flag-topped bamboo sticks to mark out a safe path for us along the way.

Natural wonder

It took us over an hour riding over rough sastrugi (wind-carved hills in the snow surface) before we arrived at the glacier. It was an amazing spectacle to see this mighty river of ice flowing down from the centre of the ice sheet trough a 10 km wide gap in the Sør Rondane Mountains.

The glacier, on its slow descent from the interior of the ice sheet to the sea, bends and cracks. Its surface is riddled with mostly invisible crevasses. Alain had staked out a safe way up the glacier with bamboo markers during previous trips. He carefully checked the position of each with a GPS and compared them to last year’s position. Of course they had moved. The glacier moves at a speed of 30 to 40 metres a year. It’s incredible when you think about it: ice flowing, and at such a speed!

Antarctica’s vast, unforgiving desert

We slowly made our way up the glacier towards the edge of the Antarctic High Plateau. We were more than 2 km above sea level! Between here and the South Pole, 3,000 km away, there is nothing but empty, white desert.

A vicious wind blew from the interior of the continent. “It’s the katabatic wind,” Alain explained. Cold air flows down from the interior of the ice sheet and accelerates under its own weight as it heads out to the coast of the continent.

The ride to Denis’ seismic observatory seemed to take forever. Drifting snow made it impossible to see very far ahead. We had to follow carefully behind Alain.

The data-logger is alive!

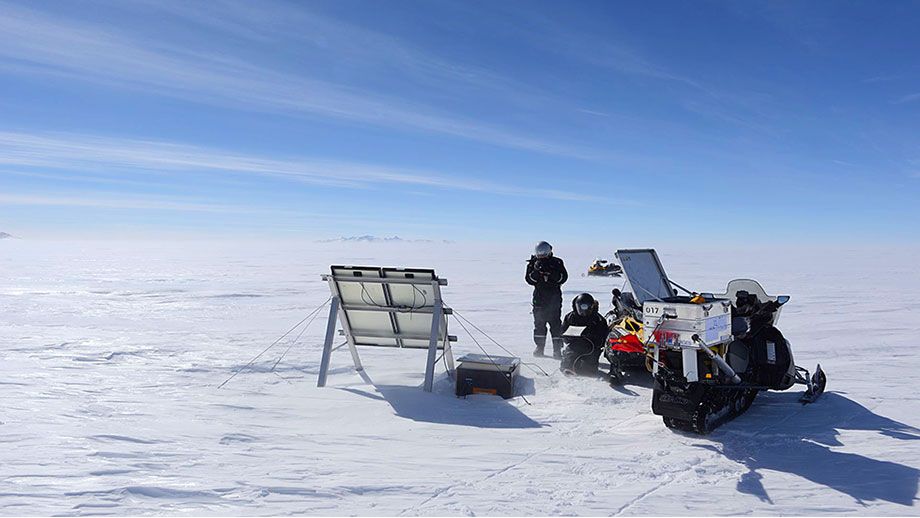

And then suddenly we had arrived. Out of the white gloom we saw a dark angular shape sticking out of the snow: the solar panel that provides energy to Denis’ instruments. The seismometer itself is buried in the ice, but the data logger and battery sit in a black insulated box above the surface.

Alain and Denis immediately got to work unscrewing the top of the box. As you know, all of Denis Lombardi’s data loggers had given up functioning sometime during the austral winter. So we thought Denis would just take out the data logger, close the lid, and we’d be off from this windy place. But lo and behold - the data logger was still working! This was totally unexpected.

Denis had to collect the data, replace the flash card, install a new battery, and reboot the system. We hadn’t even brought a shelter or tent to work in, so it wasn't easy. When we removed the lid from the data logger, drifting snow filled up the interior and covered everything with fine ice particles.

It was so cold that Denis’ rugged Toughbook computer refused to start up. His fingers hurt when he dared to take of a glove for a few seconds. We tried to shield him from the wind and the cold, but it was hard. At times I just wanted to give up and crawl under a skidoo to take cover from the relentless wind. But after an hour, Denis got the job done and we started our skidoos to make our way back.

Dress warmly, it’s cold up there!

Before leaving for the plateau, I had donned all the warm clothes I found, and put on over everything an insulated fur-hooded coverall. But by the time we started to make our way back, the balaclava I was wearing to cover my mouth had frozen stiff. My goggles were clouding over and my moustache was sporting a huge icicle, which I thought was quite funny.

The wind was now blowing hard from the right, and it was bitterly cold. Painfully cold. But there was not much I could do to protect myself from it while trying to follow in Alain’s tracks. Looking back, I should have stopped for a minute to cover my face better, but I decided not not to. Later in the day, I would come to regret that decision bitterly.

After a while the pain went away, and I was glad to see the Sør Rondanes reappearing in the distance. The second and last data logger to check for the day lay just ahead.

Dennis Lombardi found his seventh and last data logger had stopped like all but one of the others. His data are not complete. But there is hope that his seismic project in Antarctica will be saved. The manufacturer of the data logging computers has promised to try to do an emergency repair. Dennis will bring the six defective ones back with him when he leaves for Belgium on the 20th of December. The repaired data loggers will then be flown back to Antarctica on the first flight to the Princess Elisabeth station in February. Alain has promised Denis that he’ll re-install all six of the repaired data loggers again before the end of the season.

It will get worse before it gets better

When we parked our skidoos at the station’s garage, Denis asked me what I’d done to my face. “The right side is all red and swollen!” he remarked.

Concerned, I paid a visit to the station’s doctor, Jacques Richon. It turned out I had a frozen cheek. Frostbite. And very unsightly frostbite at that. Doc Richon told me that the skin would go black before it peels off, and that my cheek would swell even more the day after. He was right. This morning when I woke up, it was so swollen that I could hardly see out of my right eye.

But the Doc says the frostbite is not too serious. In a week or so, I should be fine. I have to be. I want to go to the coast!